Biography

SUCCESS

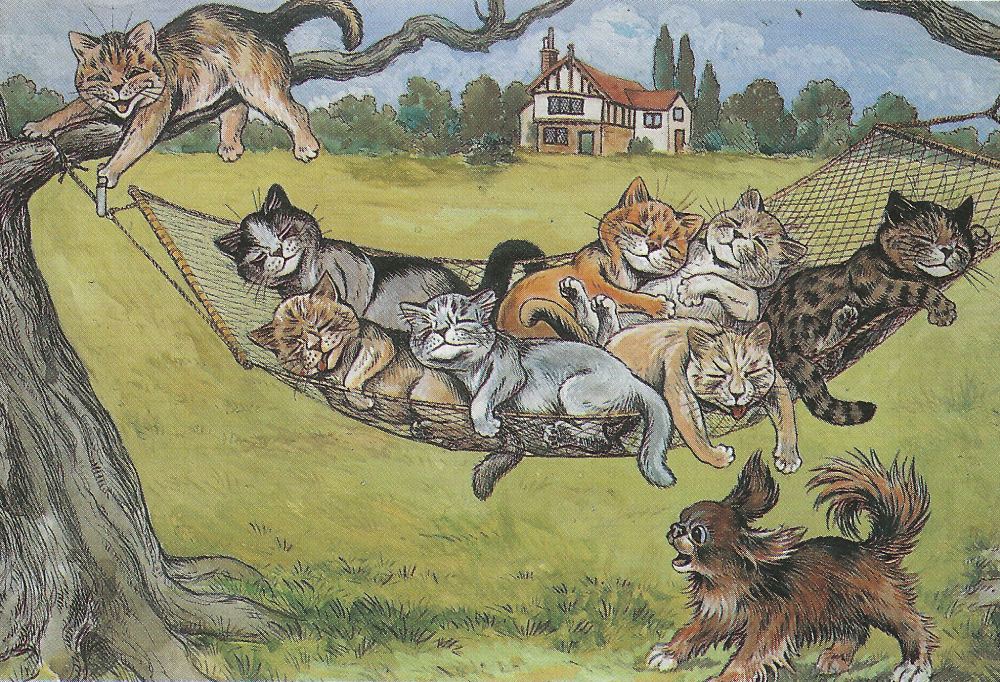

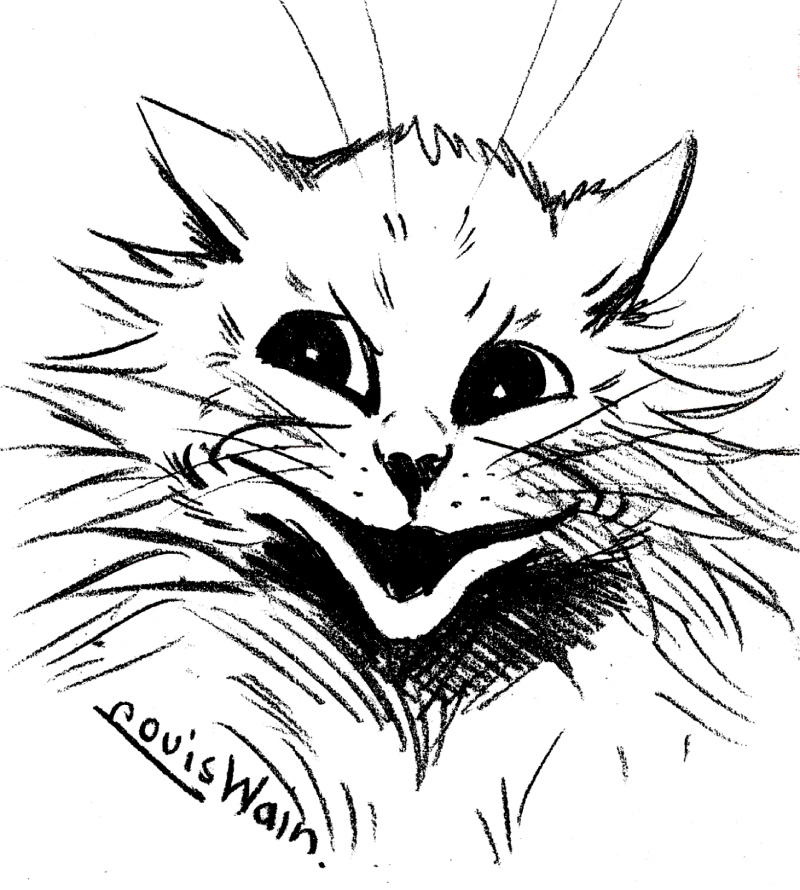

A Kittens’ Christmas Party charmed the Victorian public and proved to be the first of a steadily building success as Wain found his distinctive style and his work found a home in an ever increasing number of magazines, newspapers, and books. He took inspiration from people just as often as from cats, making preliminary sketches in public and then reinventing them in feline form. His cats started playing golf, holding concerts, going to school: while not the inventor of anthropomorphism, Wain worked the style into an artform all his own. By 1890, he became a household name, and it would be hard to find a nursery in England without one of his distinctive illustrations. Notably, in an era that tended to portray children as sentimental and proper, Wain’s cats run wild and hold a mirror of playful parody to Victorian society. In Catland, anything from a picnic to ping pong was always teetering on the edge of a sudden descent into mischief and mayhem that brought delight to the young and grown-up alike.

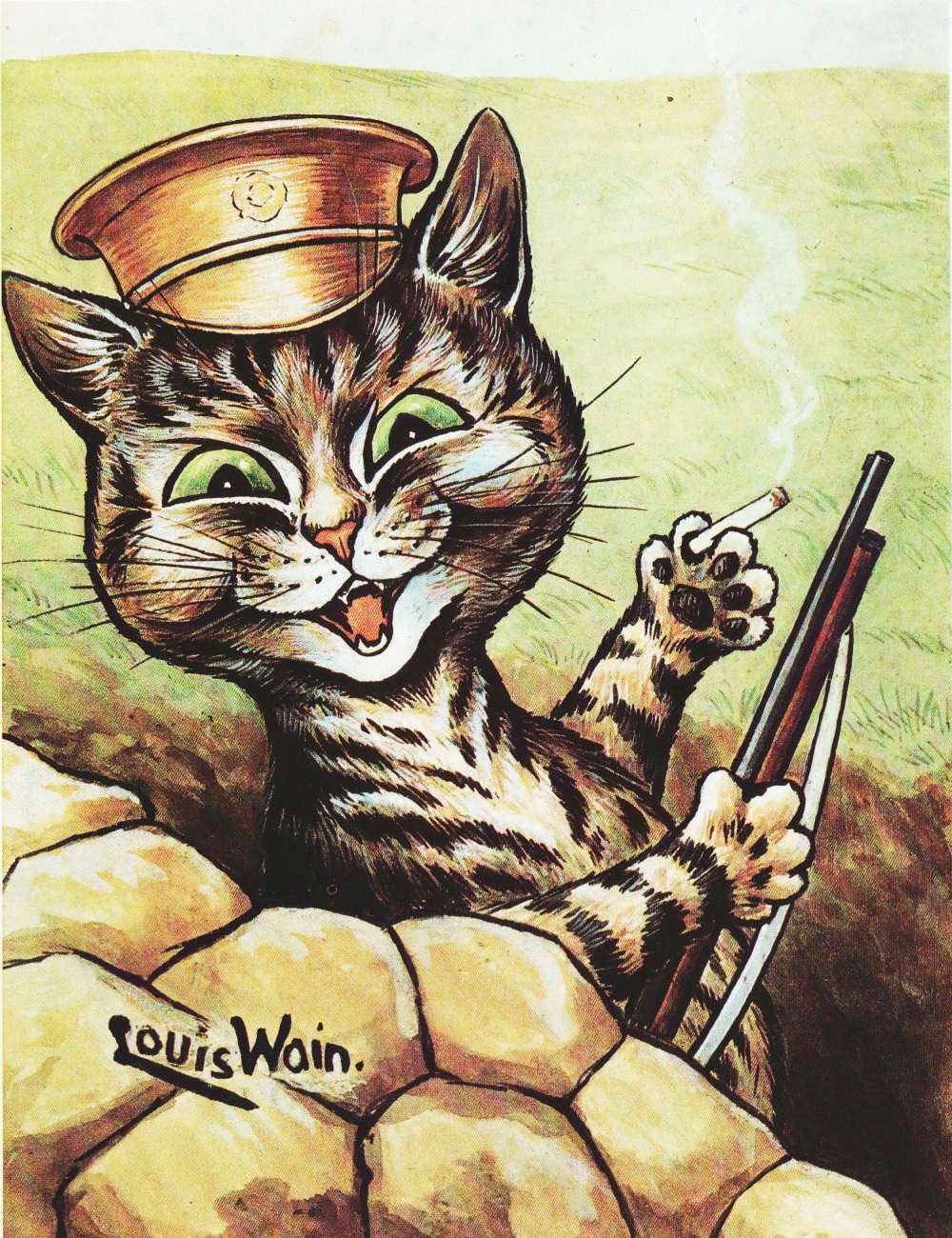

Despite what by all accounts should have been a financial success, Wain was more often than not just scraping by. On top of having to provide for his five sisters and mother, he commonly sold his illustrations directly with no thought of copyright, thus receiving few or no royalties for their republication. Beyond this, he sometimes fell for scams and charlatans, losing much of his money made during a trip to America in one such incident. Even during his 20 year run of popular annuals, he often had to pay debts with cat pictures, in addition to drawing and selling large quantities of illustrations to support cat shelters and Britain’s troops.¹

Despite what by all accounts should have been a financial success, Wain was more often than not just scraping by. On top of having to provide for his five sisters and mother, he commonly sold his illustrations directly with no thought of copyright, thus receiving few or no royalties for their republication. Beyond this, he sometimes fell for scams and charlatans, losing much of his money made during a trip to America in one such incident. Even during his 20 year run of popular annuals, he often had to pay debts with cat pictures, in addition to drawing and selling large quantities of illustrations to support cat shelters and Britain’s troops.¹

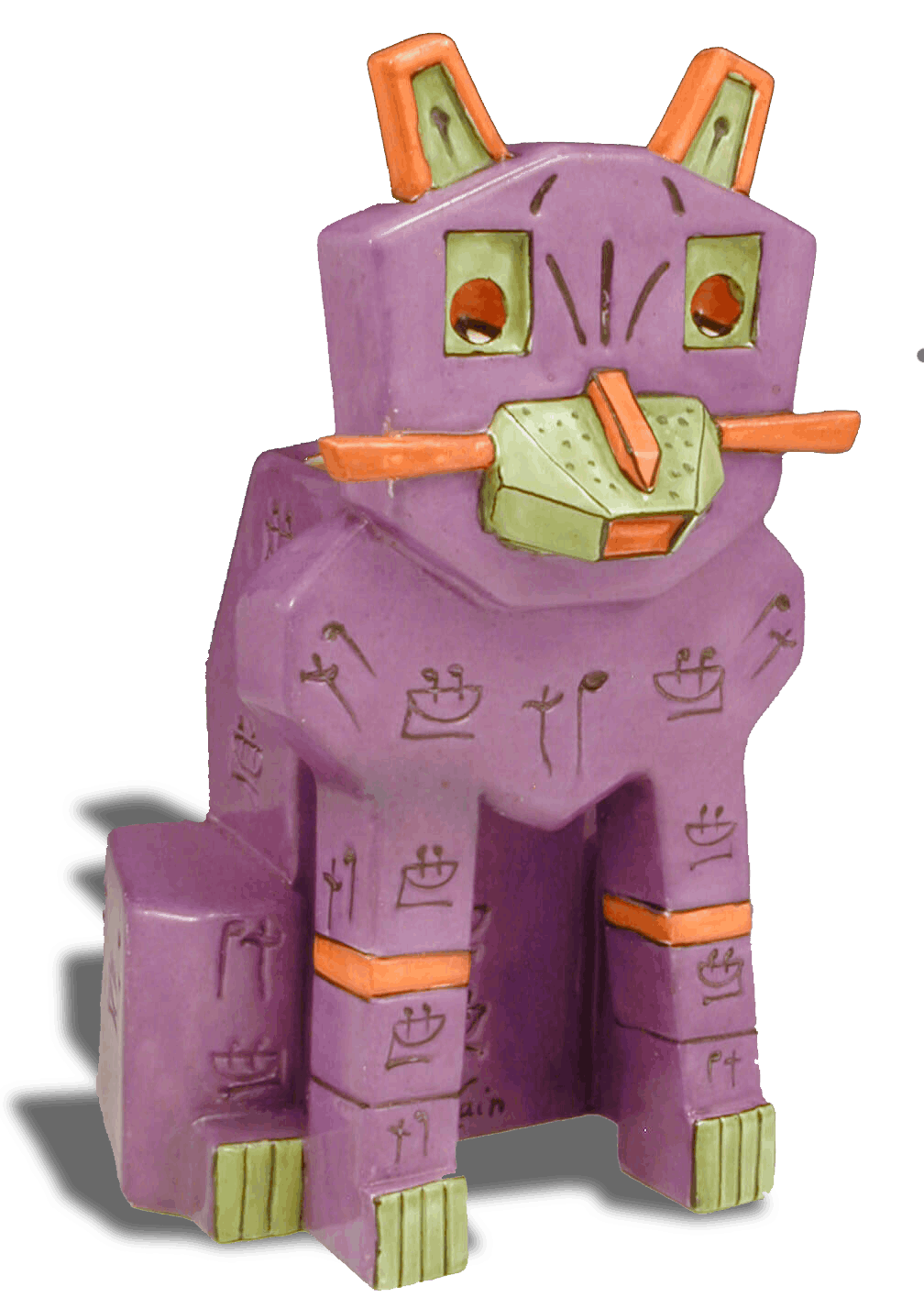

By the 1900s his popularity was waning, and the next decade brought with it a streak of bad luck. In 1910 his mother died after his return from America. His explorations into the futurist craze were literally shot down when a transport ship full of his cubist ceramic cats was sent to the bottom of the Pacific by a torpedo. His Pussyfoot cartoons, while helping lay the groundwork of later anthropomorphic animations, did not continue for long as his art style proved incompatible with the sheer number of frames that had to be drawn. Compounded by the loss of his youngest and oldest sisters in 1913 and 1917 and his steady stream of annuals ending in 1921, he entered the ‘20s with deteriorating financial prospects and strained health. However, not all was lost: he still drew just as prolifically and enthusiastically as in his earlier days, continued to illustrate the children’s books that brought delight to kits across the country, and by now was exploring themes of nature and textile patterns, hearkening both to his upbringing surrounded by such designs and the stylistic changes to come.

By the 1900s his popularity was waning, and the next decade brought with it a streak of bad luck. In 1910 his mother died after his return from America. His explorations into the futurist craze were literally shot down when a transport ship full of his cubist ceramic cats was sent to the bottom of the Pacific by a torpedo. His Pussyfoot cartoons, while helping lay the groundwork of later anthropomorphic animations, did not continue for long as his art style proved incompatible with the sheer number of frames that had to be drawn. Compounded by the loss of his youngest and oldest sisters in 1913 and 1917 and his steady stream of annuals ending in 1921, he entered the ‘20s with deteriorating financial prospects and strained health. However, not all was lost: he still drew just as prolifically and enthusiastically as in his earlier days, continued to illustrate the children’s books that brought delight to kits across the country, and by now was exploring themes of nature and textile patterns, hearkening both to his upbringing surrounded by such designs and the stylistic changes to come.

Guide

1: Beetles, C. (2011). Louis Wain’s Cats. WorthPress Ltd.

2: Dr David O'Flynn (February 7th, 2013), Louis Wain Exhibition, Bethlem Archive and Museum, SLaM [YouTube]

3: David Tibet & Paul Moody (October 18, 2018) - The Forgotten Artist Who Changed the Way We Look At Cats [Text]

4: A Celebrated Cat Artist. Mr. Louis Wain Chats with “Chums.” (1895, November). Chums, 204.